These days Bristol enjoys a vibrant and friendly LGBTQ+ scene, with a fantastic variety of gay districts and nightlife, gay-friendly accommodation, shopping and culture. Every July the city also hosts one of the best Pride events in the UK. Throughout history, Bristol has also played its own role in the liberation of queer people and struggle for equality.

To mark LGBT+ History Month, novelist and local historian Charlie Revelle-Smith from Weird Bristol looks into landmark episodes highlighting Bristol's contribution to LGBTQ+ history as well as how the city has perceived and treated LGBT+ people over time.

The story may not be as dense as that found in London or Brighton but in many ways is just as significant.

.jpg)

Image - Pride Parade, credit Paul Box

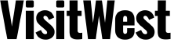

The Radnor Hotel: Bristol’s first gay pub

Tucked away on St. Nicholas Street, the Radnor Hotel (now The Radnor Rooms) may have been operating as a gay pub as early as 1925. It's believed to be the first pub to cater for a gay and lesbian clientele in the city, though its exact origins are murky as so much of LGBT+ socialising had to be discreetly hidden away before 1967.

The narrow bar had a reputation for being a raucous and decadent hangout inside – yet sombrely austere on the outside. It presented itself as an unassuming yet unwelcoming venue to those not in the know to its true purpose. It attracted a varied clientele of actors, drag queens and prominent locals who found the place discreet and safe enough to avoid the risk of public exposure.

During the Second World War the pub welcomed a new type of visitor – American soldiers based in the city. In fact it’s likely that these soldiers first introduced the American term 'gay' into the parlance of the Radnor Hotel, replacing the more common 'queer' which was in use in the 1940s.

When the Elephant opened just a few doors down in 1973, the Radnor lost all but a few of its clientele and closed as a gay bar soon afterwards, but during its 50 year history it must have been a safe haven for the people of Bristol looking to find other like-minded souls.

Image - The Radnor Hotel, credit University of Bristol

Crime and Punishment: Dying for Love

Before the legalisation of homosexual acts between men in England and Wales in 1967, various centuries have dealt with the 'problem' of homosexuality in different ways. Throughout much of the 18th and 19th centuries the punishments were nothing short of mob justice – and Bristol was no exception.

The pillory at what is now the North West corner of Castle Park was an especially cruel torture. There were six known cases of sodomy punished here with each of the men being placed in rotating stocks whereupon they were forced to walk in circles for up to an hour while they were pelted with rotting fruit and even stones. The pillory often resulted in blindness and on a few occasions even death.

If the law did not catch up with you, punishment could be metered out by your fellow citizens. In 1737 a man named only as 'a sodomite' in the local newspaper was caught propositioning a sailor in a pub on Thomas Lane. Locals were so appalled the man was dragged out into the street by a mob and beaten until he was almost killed.

One of the saddest tales of tragic romance in #Bristol history comes from 1752 when pub landlord Richard Arnold was caught in bed with stable worker William Critchett in the Swan Hotel on Broad Street. Both were hanged on St Michael's Hill for their "crime". pic.twitter.com/46oip1WV5u

— Weird Bristol (@WeirdBristol) February 14, 2019

No fates are as tragic as that which befell Richard Arnold and William Critchett. In 1752 the pair, one a former landlord, the other a footman, were caught in bed together in the Swann Inn on Broad Street and arrested. They were both hanged a few months later on the gallows at the top of St. Michael’s Hill.

Four other men are known to have been executed for this 'crime' in Bristol, though tragically, their stories have been lost to time.

John Addington Symonds: The Scandalous Intellectual

John Addington Symonds was born in Berkeley Square in 1840 (although spent most of his early years living in Clifton Hill House – now halls for the University of Bristol). As a cultural historian he would probably be best remembered for his fiercely sharp intellect and as one of the city’s leading literary critics. However, it's for his writings on male homosexuality he is undoubtedly best known.

Using ancient Greece as his inspiration, Symonds became an advocate for sexual intimacy between men as a healthy physical expression. Moreover, he argued that homosexuality could be more than what someone does and about who someone is, for the first time suggesting that the concept could be embraced as a personal identity by which someone could regard themselves.

#MuseumsUnlocked #lgbtq John Addington Symonds (1840-1893), born in Bristol, wrote about homosexuality in the late 1800s. Some of his letters are in @BristolUni collection (according to @Wikipedia his daughter, Madge Vaughan, was ‘probably Virginia Woolf's first same-sex crush’) pic.twitter.com/g7ao2OJfaL

— Ruth Hecht (@RuthHecht) July 3, 2020

Despite being married himself, his relationships with men were an open secret in high society and he seems to have enjoyed his scandalous notoriety at the time. Many of his writings went on to be regarded as the founding texts in establishing the burgeoning concept of sexual identity.

He is however now seen as a highly problematic founding father of LGBT+ rights, as in his later years he began advocating for sexual relationships between men and teenage boys, which has understandably swept him out of most discussions of early arguments in favour of homosexuality.

Despite this, John Addington Symonds can at the very least be commended for helping to start a debate about homosexuality – and one which did not begin from the presumption that same-sex attraction was necessarily a disorder.

Laurence Michael Dillon: The World’s First Trans Man

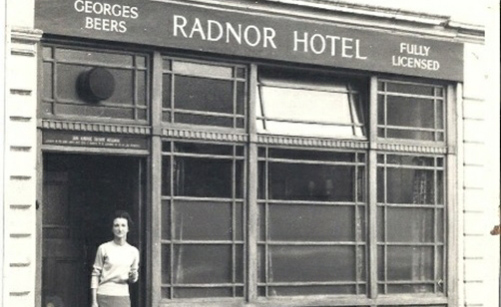

One of Bristol’s most surprising contributions to the LGBT+ story of the 20th Century is that of Laurence Michael Dillon, believed to have been the world’s first trans man to undergo gender reassignment surgery.

Born biologically female to an aristocratic family in Kentin 1915, Dillon’s birth name was Laura Maud McCliver. Dillon never felt comfortable with the gender he had been assigned at birth and always preferred wearing men’s clothing but it wasn't until 1939 when he moved to Bristol that he first began experimenting with testosterone injections.

The results were very successful and soon afterwards he discovered he was being perceived as male by strangers, to the the extent that during the war he was able to find work as a fireman. For the first time in his life he began feeling comfortable in his body.

After the war, following a chance encounter with a doctor named Harold Gillies who specialised in reconstructive surgery on the genitals of injured soldiers, Dillon began a series of operations. He was treated in secret at the Bristol Royal Infirmary, including the world’s first phalloplasty surgery.

Image - Laurence Michael Dillon

Following several years living as a man, he was exposed by the press who were researching his aristocratic connections during an inheritance dispute and finding only 'Laura Maude' listed as the heir to the family fortune. Shamed by this intrusion into his personal life and the following notoriety, Dillon fled to India where he seems to have found his true home, even becoming the first ever white European man to be ordained as a Tibetan Buddhist.

Dying of an unknown illness at the young age of 47, Dillon’s short life would pave the way for scores of others who felt their bodies were at odds with their true genders, as would the groundbreaking work performed by Harold Gillies (who would go on to specialise in gender reassignment for both men and women) at Bristol Royal Infirmary.

Advocates, Allies and Art: Arnolfini

Few institutions have been such loyal advocates of the LGBTQ+ fight for equality as Arnolfini – Bristol’s contemporary arts centre. In the face of much public hostility to the 1977 Pride parade, the Arnolfini scheduled a season of gay-themed events and film screenings in solidarity, firmly aligning itself with the early years of the movement.

However, it was during the build up to the enactment of Clause 28 in 1988 when this friendship was firmly cemented. Clause 28, introduced by Margaret Thatcher’s government (and masterminded by Bristol-born MP David Wilshire) was intended to prevent the 'promotion' of homosexuality in schools. The vague wording worked to virtually prevent any and all discussion of homosexuality in schools.

The meeting, organised by the Arnolfini, proved so popular it had to be moved to the cinema to accommodate the unexpectedly large crowds. From here large scale protests were organised for College Green and Broadmead.

Clause 28 was abolished in 2003 and the Arnolfini has continued its long standing relationship with Bristol’s LGBT+ community ever since those early days of the burgeoning movement, allowing people to come together in safety and with a simple hope to fight for equality.

.jpg)

Image - Arnolfini

About the author

Charlie Revelle-Smith is a Bristol based novelist and local historian. To learn more about the secret and lesser known history of Bristol from Charlie, you can buy his two Weird Bristol books and follow @WeirdBristol on Twitter and Instagram.

to add an item to your Itinerary basket.

to add an item to your Itinerary basket.