If people have heard of Bristol-born eighteenth-century poet Thomas Chatterton (1752–1770), it is most often in terms of his tragic death aged just 17— as depicted in an oil painting by Henry Wallis.

For too long this has been the case, overlooking what is an actually fascinating life; Chatterton not only a likely child prodigy born into poverty, but a poet, political writer and forger; often going under the pen name of an imaginary fifteenth-century monk Thomas Rowley, and trying to pass off his work as from that era!

Nicknamed Bristol’s Shakespeare, he is most well-known for his Medieval-style poems, which he claimed to have discovered in a chest in a room above St Mary Redcliffe Church and passed off as belonging to a (fictional) 15th century monk, Thomas Rowley.

Chatterton left Bristol to pursue his writing career in London in April 1770. Just four months later, he died in what was once thought to be a suicide after his failure to find success and wealth but is now considered an accidental overdose. Either way, his death at such a tragically young age was part of what cemented his legacy as a romantic figure.

Image: Henry Wallis ‘Chatterton' 1856, credit Tate CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (unported)

Controversy over who had authored his works followed his death, as few people believed they could be written by someone as young as Chatterton. Eventually, it was accepted that the Rowley poems were his and Romantic poets such as Wordsworth, Coleridge, Keats and Shelley would later be influenced by his story and writing.

With help from Bristol Poetic City, we explore Bristol locations with connections to Chatterton’s life and legacy below:

Chatterton’s school and birthplace

Chatterton was born in the schoolmaster’s house of Pile Street School in 1752. Born to a single mother (his father – a writing master at the school – died before his birth), he grew up in poverty and the family moved away to a relation’s house on Redcliffe Hill after Chatterton’s christening in 1753.

He briefly attended Pile Street School but was turned away as his teacher thought he was too ‘dull’ to keep up with lessons. A short time later he would become a precocious student at Colston School, fascinated by the medieval period. By the age of 8 was said to enjoy reading and writing all day independently, and by 11 was contributing articles to the Bristol Journal, seeking out new books to read wherever he could.

Pile Street School was demolished when the street was widened to become Redcliffe Way but the building’s façade was attached to the former schoolmaster's house that stood behind it. Today, you can see a commemorative plaque here as well as step inside for a taste of fresh Italian food at La Panza.

St Mary Redcliffe

The magnificent St Mary Redcliffe Church inspired Chatterton’s early writing and the creation of the medieval monk, Thomas Rowley.

Chatterton's uncle was the Sexton at the church and it was a place where various literary materials could be accessed, including Bibles (which Chatterton read thoroughly), as well as historic artefacts—the boy reportedly fascinated by the historic inscriptions and designs on tombs, furniture and the wider architecture of the church. In the Muniment Room of the church, Chatterton’s father discovered a range of medieval parchments hidden in some oak chests, and it was these that became the inspiration for his medieval-styled mysteries and the forged identity of Thomas Rowley he would go onto create.

A memorial monument to Chatterton used to stand outside the church but was demolished after falling into disrepair and the figure of him that was on top is now in Bristol Museum’s store. The Muniments Room from where Chatterton’s father had been allowed to take old papers to research his family history is now referred to as the Chatterton Room.

The church is open to visitors from 8.30am until 5pm Monday to Saturdays or 9am until 4pm on bank holidays – go along to admire the church’s fine gothic architecture, learn more about its place in Bristol’s past and discover why it was a source of inspiration for Chatterton.

Image: St Mary Redcliffe

In 1769 Chatterton, aged 16, approached one of the most significant and well-known supporters of the Gothic, Horace Walpole who not only built his own Gothic villa, Strawberry Hill in Twickenham, but he also penned a Gothic novel: The Castle of Otranto (published Christmas Eve 1764). Chatterton, over the course of a number of letters, sent and sought Walpole’s help in publishing the fragments of his Rowleian poetry (and the select work of others from the fifteenth century). Walpole, however, wasn’t convinced by the manuscripts’ authenticity. He refused to offer the support that Chatterton was after, and Chatterton’s Rowley corpus wasn’t published until 1777—7 years after his death.

Chatterton’s poetic forgeries were hardly credible as fifteenth-century relics, even though a number of people went to lengths to attempt to prove their authenticity. Indeed, they follow the polished formula of eighteenth-century poetry, but the words are replaced by older examples, and there is a widespread revision of spelling (including doubling up on letters, substituting letters, and also sprinkling the letter ‘e’ liberally through words).

Not only was Chatterton interested in poetry, but also by other medieval arts, including heraldry. Calligraphy was also crucial to his forgery of the poetry; he adopted a curious historic script in which to write what he claimed was material from the fifteenth century.

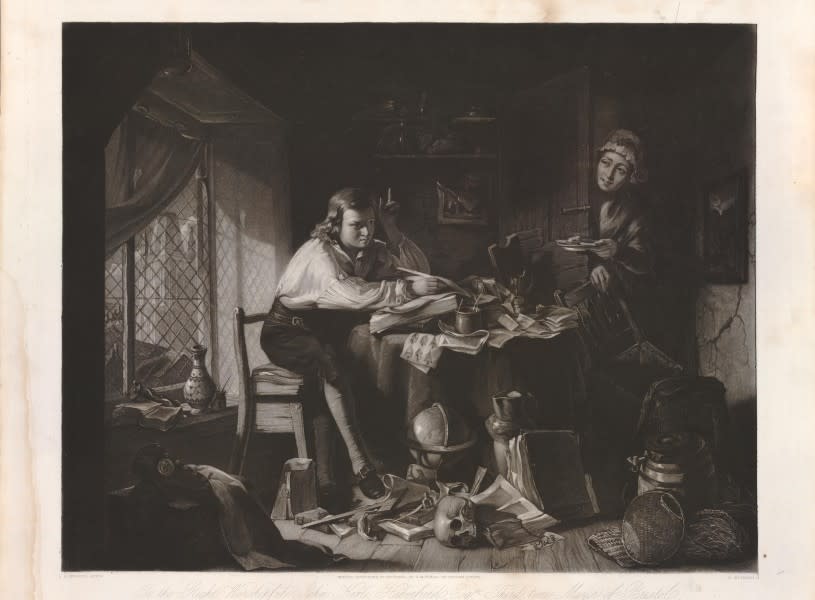

The centrality of such art forms to his forgeries is clearly demonstrated in Richard Jeffreys Lewis’s painting, Chatterton Composing the Rowley Manuscripts. Prints made after this painting were in circulation, and the teenage Chatterton is at the centre of the composition.

Loose fragments, including depicting heraldry, are found all around, as are large books and collections of manuscripts. In the foreground is the fabled chest that his father liberated from St Mary, Redcliffe, and the church’s tower can be seen through the window behind Chatterton. This really sums up the Gothic nature of his impostures.

Image: Chatterton Composing the Rowley Manuscripts

Bristol Beacon

Near to the city’s largest concert hall once stood Colston School, which Chatterton attended as a charitable pupil from 1760. The school had been founded c1708 by Edward Colston, a merchant and philanthropist who made much of his wealth through the transatlantic slave trade, to provide pupils with a basic education and a route into local apprenticeships.

Plaques and statues

Dead at seventeen, Chatterton was at first considered a rogue and scoundrel for having made forgeries, but soon his reputation became that of a child genius. How could, for example, a sixteen-year-old child create such fantastic historical impostures? Today, he is remembered as a genius, and one with a prodigious imagination and capacity for learning.

A plaque related to Chatterton’s literary legacy lives on number 49 of the High Street in the city centre, marking the location of Joseph Cottle’s publishing business in the late 18th and early 19th century. Many of the first key Romantic works were published here and it’s also a stone’s throw from the birthplace of a prominent Romantic poet, Robert Southey. Although Southey’s original house at 9 Wine Street is no longer there, a plaque has been placed on a building in a similar spot today.

It was Cottle and Southey who collaborated on the publication of an edited collection of Chatterton’s work in 1803. Southey also lived with Samuel Taylor Coleridge in Bristol for a period of time, who wrote the poem ‘Monody on the Death of Chatterton’.

A bust of Southey was created in his honour in 1843 and is still on show in the north choir aisle at Bristol Cathedral, where Chatterton’s father was once a chorister. A five-minute walk away in Millennium Square is also a bronze statue of Chatterton by Lawrence Holofcener.

Over in Cliftonwood, a plaque on what is now Brandon House commemorates the site of the Jacob’s Well Theatre, Bristol’s first purpose-built playhouse that opened in 1729. Chatterton wrote disparagingly about the theatre, describing it as “…a hut in Jacob’s Well… A mean assembly-room absurdly built…”. While true that it was small in size, the theatre actually played a big part in the local arts scene – stars of the day performed there and guests included well-to-do visitors to the spa at nearby Hotwells.

Discover more about Bristol’s role in the Romantic movement on the Bristol and Romanticism walking tour, a self-guided walk in the footsteps of poets from the time.

Read more