On the anniversary of the beginning of the Bristol Bus Boycott in 1963, Dr Roger Griffith MBE writes about this landmark event.

The 1963 Bristol Bus Boycott was a landmark event for British civil and legal rights. Campaigners, vexed from signs that read ‘No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs’, fought for racial equality and social justice. Their protests led to the end of ‘the colour bar’ which banned Black and Asian people from driving buses. These actions would pave the way for the Race Relations Acts in the 1960s and the UK 2010 Equality Act, which protects the rights of people across nine characteristics: race, sex, religion, gender, marriage, pregnancy, age, disability and sexual orientation.

St Pauls & Windrush

People from the Commonwealth were invited guests to help rebuild the UK after World War Two. In the early 1960s, Bristol had a vibrant West Indian community, with many living in St Pauls and Easton. They encountered racism and discrimination in housing, employment and social life. Some suffered racist violence from gangs of white youths known as Teddy Boys. In response they set up their own churches, clubs and associations.

In 1963 the Bristol Omnibus Company refused to employ Black or Asian staff following a decision by Transport General Workers Union (TGWU; today known as Unite, who apologised formally in 2013). The local community formed the West Indian Development Council, including Owen Henry, Audley Evans, Prince Brown and Guy Bailey and with Paul Stephenson as spokesman. Several women, including Barbera Dettering, supported the boycott as well as forming several institutions in Bristol that remain today including St Pauls Carnival.

Image - Roy Hackett Mural in St Pauls (no longer visible) - CREDIT Sam Saunders

The Bristol Bus Boycott

Paul Stephenson set up a test case to prove the colour bar existed, arranging an interview with the Bristol Omnibus Company for Guy Bailey. When the Company discovered Guy was Black the interview was cancelled. Inspired by the protests of African-American Rosa Parks in Montgomery, Alabama, that brought Martin Luther King to prominence, the Bristol-based campaigners began a bus boycott, holding a press conference on 29 April 1963.

The then Trinidad High Commissioner and famous West Indian cricketer Sir Learie Constantine supported the movement, and the campaign gained international headlines. Many white Bristolians, including students from the University of Bristol, marched and led in front of buses at Lawrence Hill. This unity would provide a template for protest in the city against the violence of the far right, SUS laws and Apartheid.

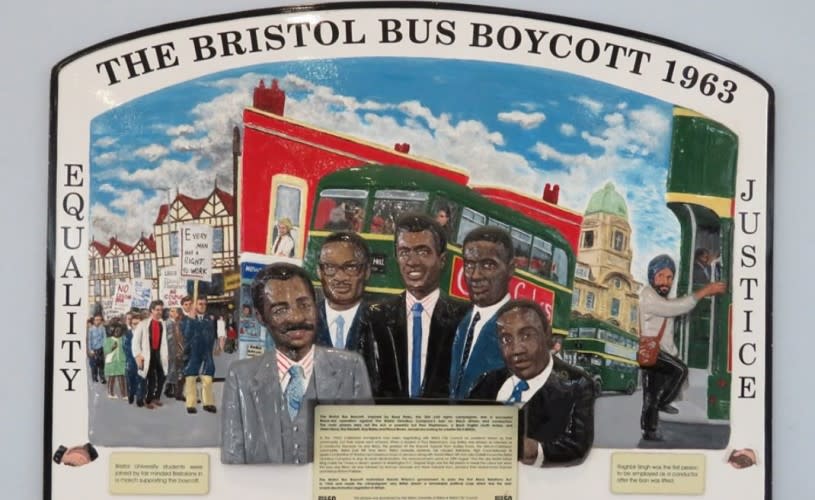

Image - Bristol Bus Boycott Plaque at Bristol Bus Station

Resolution

On 28 August 1963, the TGWU announced the end of the colour bar. It was the same day that Martin Luther King made his famous "I Have a Dream" speech in Washington D.C. On 17 September, Raghbir Singh, a Sikh, became Bristol's first non-white bus conductor and later Norman Samuels became the first bus driver of West Indian origin.

Impact & Influence of the Bristol Bus Boycott – UK Equalities Laws

Tony Benn, who was the Bristol East MP, was a prominent figure and ally. Benn worked with the West Indian community before serving in Harold Wilson’s government and helped pass the first UK equality act. The 1965 Race Relations Act made "racial discrimination unlawful in public places" and was strengthened in 1968 to include housing and employment. It is acknowledged as the founding block in subsequent British equality laws and its legacy is the current 2010 UK Equality Act.

Today there is a plaque in recognition to the brave campaigners at Bristol Bus station, provided by First Bus. Paul Stephenson, Roy Hackett, Guy Bailey and Barbara Dettering have all been recognised with local awards and national honours and the Seven Saints murals commemorate other Bristol leaders.

Read more: