In this guest article, Bristol bridge aficionado Jeff Lucas delves into the stories behind four bridges you might not know much about…

Most people know at least something about Bristol's iconic Clifton Suspension Bridge. You may, however, be surprised to learn that Bristol has a total of 45 bridges that cross its main waterways that can be crossed on foot.

From Brycgstow to Bristol in 45 Bridges is a book by myself, Jeff Lucas, and Thilo Gross that tells their fascinating stories and the part that each one played in the history of the city – a history which began with a bridge built here across the Avon 1000 years ago at the Anglo-Saxon settlement called Brycgstow – ‘The place of the bridge’.

Thilo and I have linked the bridges together into a 26-mile circular walking route – the Bristol Bridges Walk – that takes you over all of them, from the nooks and crannies of the inner city to the open vistas of the Severn Estuary and back again. You can download the instructions/map/gpx file for the walk (or cycle-ride) for free.

The Bridges Walk is also a solution to an intriguing mathematical puzzle known as ‘The Königsberg Bridge Problem’: how to walk over a given set of bridges without crossing the same one twice. Thilo, a lecturer in mathematics, explains in the book the importance of ‘The Bridge Problem’ to the modern world and how he solved it for Bristol.

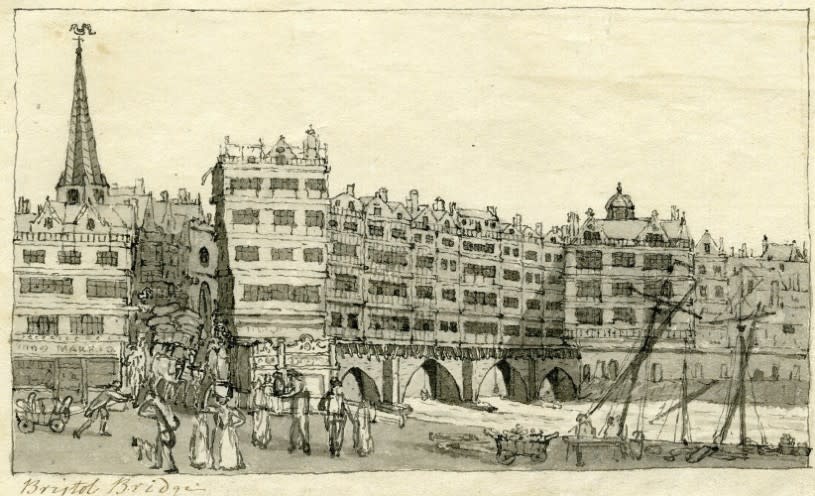

Bristol Bridge

The current Bristol Bridge (Fig 1) in the heart of the city by Castle Park occupies exactly the same spot as did the very first Bristol Bridge around the year 1000AD. This first bridge was replaced in the year 1247 by a stone bridge with pointed Gothic arches. It was soon extended outwards and upwards in very grand style with shops and houses five stories high which lined the central roadway – a London Bridge in miniature (Fig 2). This 3D computer model ‘flythrough’ gives you an idea of what it was like.

Fig 1 - Bristol Bridge today, credit Jeff Lucas

Bristol Bridge then stood intact and largely unchanged for nearly 500 years until the mid 18th century. By that time, traffic had increased in volume, size and weight, and the width of the roadway had been narrowed down by the buildings either side. The bridge became congested and dangerous – there were serious accidents, some fatal. In 1758, James Bridges (good name!) was commissioned to design and build a replacement bridge, which took 10 years to complete owing to much argument and controversy and the extensive preparation work needed.

Fig 2 - Bristol Bridge in the 14th century

In the Victorian era, the bridge was much altered. It was widened with ironwork 'wings' resting on iron columns. The four huge stone toll gates which used to stand one at each corner of the bridge were demolished and it lost its elegant high stone balustrades. Nevertheless, all of the stonework we see today is the core part of James Bridges’ design of 1768. Now that cars have recently been prohibited from using it, Bristol Bridge has once again become as peaceful as it once was 1000 years ago!

Meads Reach Bridge

A 10-minute waterside stroll eastwards from Bristol Bridge takes you to one of the city's newest bridges, built in 2008. The high-tech stainless-steel Meads Reach Bridge (Fig 3) is known as the ‘cheese grater’ because of its 55,000 tiny perforations in its surface. This is a fine example of how a bridge may be both a piece of engineering and also an elegant work of art.

Fig 3 - Meads Reach Bridge, credit Jeff Lucas

Meads Reach Bridge was designed with 3D computer modelling software usually used for aircraft wings. It’s a ‘stressed skin’ design, which means that all the visible surface is contributing to its strength. It was assembled in sections on the riverbank into a single 75-tonne piece and then craned into position across the water. An important design intention was that the bridge should not just be lit but should be the light. At night, internal lighting streams out from the perforations in the surface, creating a magical sight.

Sparke Evans Park Bridge

A half-mile east of Temple Meads is one of Bristol's most attractive footbridges – Sparke Evans Park Bridge, (Fig 4) which spans the Avon between the Paintworks development and Sparke Evans Park. It’s a light, elegant miniature suspension bridge with steel basketweave balustrades, made in 1933 by the Bristol iron and steelmakers John Lysaght and Co. It was assembled by local labour as one of many job creation schemes implemented by the city council to alleviate unemployment in the great depression years of the 1930s.

Fig 4 - Sparke Evans Park Bridge, credit Jeff Lucas

It is the bridge's leafy setting with its backdrop of Sparke Evans Park that make it such a delight – especially when autumn colours arrive. Keep an eye out for tufted ducks, coots, mallards and moorhens rummaging around the riverbanks. This bridge was designed by the London firm of David Rowell and Co who specialised in simple iron framed buildings and small bridges. Rowell's structures were intended to be easily assembled by unskilled labour from kits of parts shipped to the site. They were therefore often used in the British colonies and other remote parts of the world.

If you ever find yourself on the tourist trail in the Torres Del Paine National Park of Patagonia, you may well drive across Il Punte Negro – ‘The Black Bridge’ (Fig 5) – a small Rowell suspension bridge very similar to our own. Rowell's travelling salesmen certainly got around!

Fig 5 - Il Punte Negro (The Black Bridge) in the Torres Del Paine National Park of Patagonia

Bathurst Basin

Part of the Harbourside, Bathurst Basin is a quiet spot for a pint at The Ostrich (one stop on the Weird Bristol pub crawl) next to the modern footbridge (Fig 6) at the north end of the Basin. But on the morning of 21 November 1888, a predecessor of this bridge was engulfed in a spectacular explosion and fire.

Fig 6 - Bathurst Basin, credit Jeff Lucas

A large cargo-carrying sailing boat with a crew of four was moored near the bridge on the west side of the basin, waiting to go through the lock at the south end (now disused) into the New Cut and then out to sea. It was carrying 300 barrels of naptha, a highly flammable liquid similar to petrol.

At around 11.20am a policeman, who had come aboard a little earlier to satisfy himself that all was well with the cargo, stepped off the boat. As he turned and walked away there was a gigantic explosion behind him which blew the boat into matchwood, instantly killing three of the crew and sending flames higher than the tower of the General Infirmary on the other side of the basin. Every pane of glass facing the Basin in that building was blown in – 1000 in all. Since naptha floats on water, most of the Basin became a sea of flame, engulfing the footbridge.

Amazingly the policeman was uninjured, the fourth member of the crew was fished from the water with just a broken leg and no members of the public were hurt. In a short space of time, hundreds of spectators crowded the quaysides to watch the inferno (Fig 7). The fire brigade, with their rudimentary equipment, could only look on and allow the fire to burn itself out. The bridge suffered remarkably little damage and was soon back in operation.

Fig 7 - The Bathurst Basin naptha explosion. Hundreds of people watching the flames on the water.

A subsequent inquiry concluded that one of the naptha barrels must have leaked and that one of the crew had probably struck a light for a smoke, igniting the explosive vapours. The Docks Board moved quickly to prohibit the movement of all flammable liquids through the Floating Harbour.

If these stories of Bristol's ‘other’ bridges have sparked your interest, then check out the Bristol Bridges Walk Challenge Facebook Group. Join the group and you can find lots more information by clicking on the Files tab of the group's homepage. And if you complete the whole walk, you can get a badge to mark your accomplishment!

About the author

Jeff Lucas read sciences at the University of Leicester and obtained a postgraduate degree at Leeds in 1974. He lived in Bristol for 25 years before moving to Portishead after retirement from a career in occupational health and safety. He is a long-standing member of Bristol Civic Society and was their events organiser for several years. He has led walking tours for the Society through various parts of the city.

Jeff is a keen amateur photographer and took all the photographs in the book. His work has been shown in the Royal West of England Academy Open Exhibition and he has received a commendation in the Sony World Photography Awards. He regularly exhibits photographs as a founder member of the Portishead Arts group of artists.

You might also like: