Local author of the Weird Bristol history books, Charlie Revelle-Smith, takes us on his personal tour of some of Bristol’s macabre and gruesome history. From haunted pubs to bloody murder, wrap up warm and retrace the steps of our city’s darkest days…

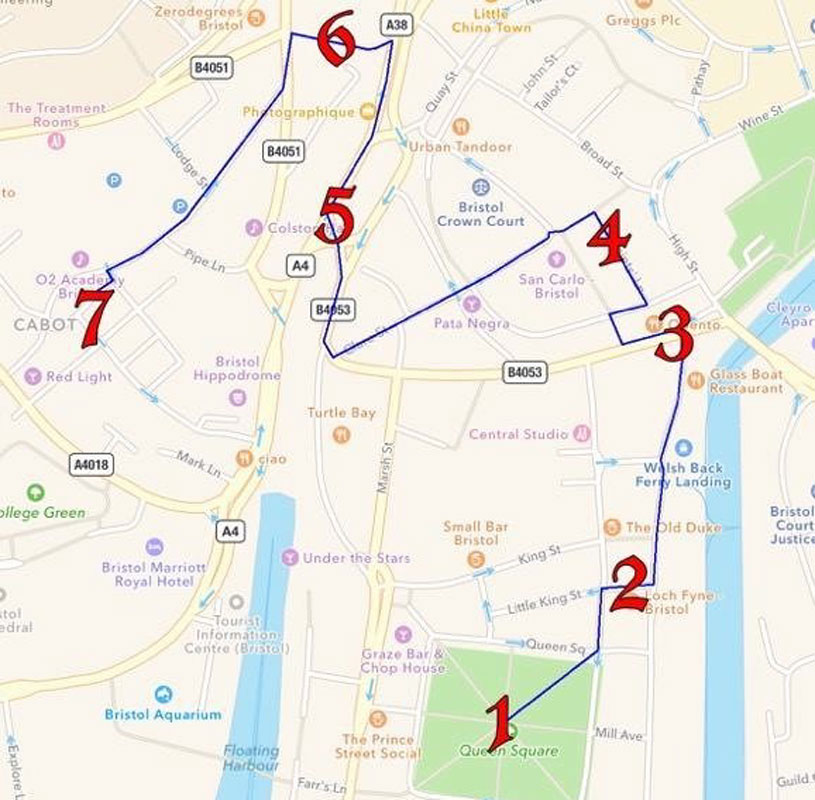

The Tour Map

The route is approximately two miles and is mostly a level walk, with the exception of the steps from Baldwin Street and Christmas Steps. It is paved throughout and should take no longer than an hour.

1. Queen Square

Our journey into the dark heart of Bristol begins in the middle of Queen Square, the beautiful garden park in our city’s centre. Built between 1699 and 1727, the square was named after Queen Anne and remains a popular, verdant getaway from the bustle of urban living.

Looking from the statue of William III to the north end of the square, evidence of the bloody history of the area can be found in the comparatively modern buildings that line this side.

Image - Queen Square

The Bristol riots took place here over three days and nights in October of 1831 and were sparked by the injustice and political exploitation of the people of Bristol. Of the population’s 104,000 residents, only about 5% were eligible to vote and the city had become known as a 'rotten borough' - rife with corruption and the suppression of its people. Following a visit from a local magistrate who was opposed to reform of the voting system, a mob of angry residents chased him to a house in Queen Square.

Rioters soon swelled in number to over 500 men who torched and looted much of the property and destroyed most of the north side of the square. Following the riots five men were arrested as the supposed instigators, four of whom were sentenced to death, (the fifth deemed 'an idiot' and unfit to stand trial was transported to a penal colony in Australia). The men were hanged at the gates of nearby New Gaol Prison and their bodies were left dangling for many days as a warning to any would-be rebels of the fate that would befall them.

Make your way to Queen Charlotte Street at the north-east corner of the square.

2. The Llandoger Trow

The Llandoger is the large, historic pub on the intersection of Queen Charlotte Street and King Street. Built in 1664, the pub was once considerably wider but was partially destroyed during the Bristol Blitz of World War II.

The Llandoger Trow is probably best known for its literary pedigree, being both the real world inspiration for the Admiral Benbow in Treasure Island and also the place where Daniel Defoe heard the tales of castaway sailor Alexander Selkirk, which would inspire him to write Robinson Crusoe.

Image - The Llandoger Trow

Among its more notorious patrons was likely to be found a young Edward Teach, a seemingly ordinary Bristolian who the world would come to know as Blackbeard, the most feared pirate on the seven seas. Blackbeard was a ruthless mercenary who was rumoured to set fire to his own beard in battle in order to appear even more ferocious. Tales were told that the beheaded Blackbeard was able to swim around his own ship seven times before dying.

While the legends of Blackbeard have certainly been exaggerated, it is perhaps the more ethereal residents of the Llandoger who are among its most intriguing. The pub is believed to be one of the most haunted in the world, with up to fifteen ghosts reported over the centuries. The most memorable - and saddest - of these spectres is that of a small boy known as Pierre who walks with a pained limp and a caliper on one leg. He is often seen staring mournfully from the upstairs windows at the living patrons in the street below.

From the Llandoger, follow the harbour along Welsh Back to the corner where it meets Baldwin Street.

3. Bristol Bridge and Castle Park

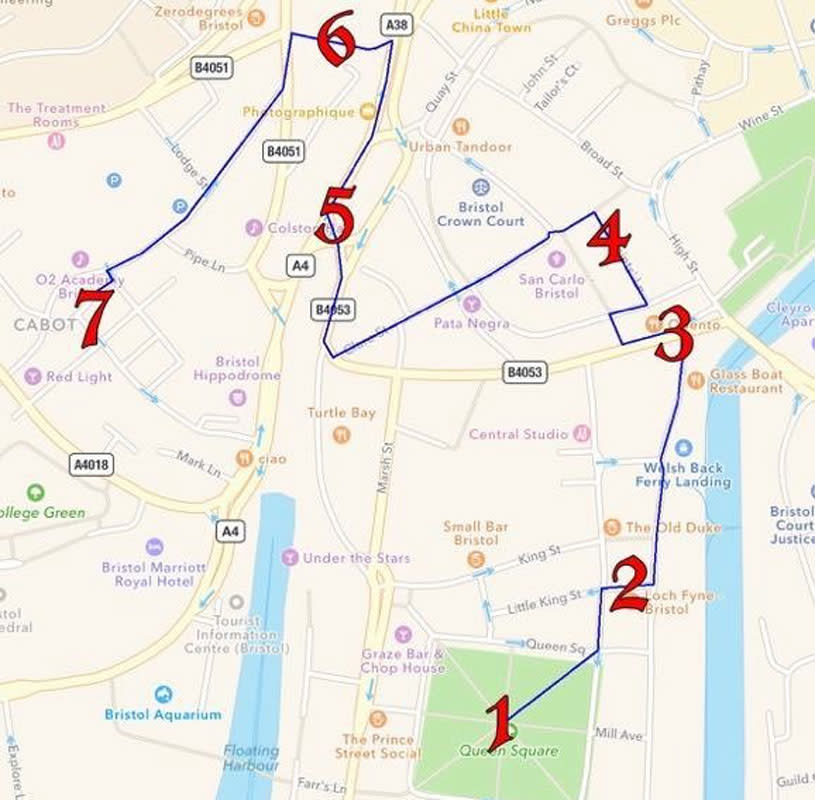

You are now standing at one of the most historically rich locations in the city. There has been a junction and bridge here for as long as there has been a Bristol and though both have gone through radical changes over the years, they still give some hint of the vital importance they once served, in fact, the first bridge standing over what was then the original path of the River Avon (and boundary of the city) gave our city its name; Bristol derived from the old English word Brigstowe - literally meaning 'Place of the Bridge'.

By the 17th century the bridge was a bustling hub, lined with five storey buildings along its breadth. It was also a dangerous location with collisions between pedestrians frequent and of-ten fatal. It also provided copious dark alleys and shadows for highwaymen to hide, and the robbing of wealthy travellers was common.

Image - The old Bristol Bridge

By 1793 the situation was so bad that plans were drawn up to demolish the buildings along the bridge and to levy a toll on anyone crossing. This was seen as such an outrage that a tremen-dous riot erupted, resulting in the deaths of 11 people and injuries to a further 45. It remains the bloodiest riot in the history of our city.

Bristol’s status as a port of international importance left it vulnerable to the ravages of disease carried in by sailors and their goods and none were more devastating than that of the bubonic plague. Bristol was the first city in Britain to fall victim to the illness, which presented in painful swelling, fever, black hives and very often death. Some believe that its port may have been the route by which the Black Death was able to spread through the country.

The epidemic came in several waves, beginning in the 14th century, and would go on to claim between one half and two thirds of the city’s population, mostly in the area of the Old City where you are now. It is rumoured that deep beneath what is now Castle Park and part of what is now Broadmead lay the remains of thousands of victims, buried in pits outside of the city wall, though there has been scarce archeological evidence to support this story.

From here, follow Baldwin Street to the steps between Old Fish Market and Revolution.

4. St. Nicholas Street

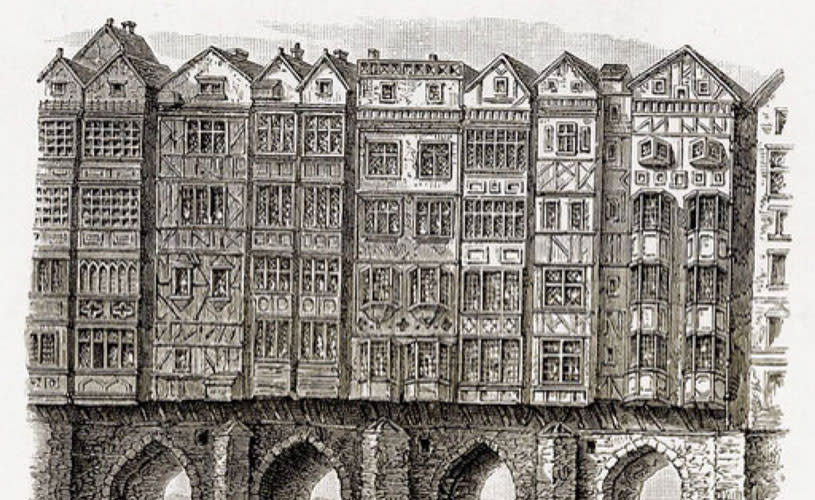

Climb the steps where you will find Mugshot Bristol, the unlikely setting for one of Bristol’s more intriguing mysteries. On the exterior of the building are the sculpted heads of four people, the third of which is the haunting 'veiled lady' - a mysterious figure whose symbolism has been lost to time. Some believe she and the three other figures may represent the seasons, with her being autumn, while others have suggested that she is a rare example of death being presented in the guise of a woman.

Image - Mysterious figure on St Nicholas Street

Follow All Saint’s Lane from here alongside St Nicholas Market until you come to All Saint’s Church. This elegant and compact building was once at the heart of Bristol’s plague ravaged centre and most of the west side of the church is the original 12th century structure. The church is said to be the haunt of the ghost of a man whose very appearance was enough to frighten witnesses half to death.

Members of the family living in the adjoining household to the church during the mid 19th century claimed to hear heavy footsteps as the ghost stomped about the staircase and even on one occasion manifested as lights which danced across the wall. However, the ghost seemed to be particularly threatening towards one maid who repeatedly told of the horror of hearing her door unbolt from the inside late at night and a figure entering the room wearing ancient robes and long whiskers who would proceed to shake her bed and claw at her sheets.

Follow the lane to where it meets Corn Street, then turn left and follow the road downhill to St. Augustines Parade.

5. The Statue of Edward Colston

At St. Augustine’s Parade, carefully make your way northwards (with the Floating Harbour behind you) until you come to the former site of the imposing statue of Edward Colston (1636-1721). No tour of the dark corners of our city would be complete without at least touching on the darkest of all chapters in our history.

The statue of Colston, by sculptor John Cassidy, was rendered in bronze and was unveiled in 1895. At an impressive 18 feet tall (including the plinth) Colston looked pensively across the jumble of busy intersections of St. Augustine’s Parade. At first it may have been hard to imagine how this man could have come to be one of the most divisive and controversial in Bristol’s history.

Colston was a merchant and MP who gifted the city many almshouses, schools and even a hospital, all of which pales into insignificance in the eyes of many when compared to the role he played in the 'trade' of transatlantic slavery. As deputy governor of the Royal African Company, he was part owner of one of the largest businesses involved in the detestable trade of humans and though the inscription at the base of the statue read 'Erected by the citizens of Bristol as memorial to one of the most virtuous and wise sons of their city' in recent years the people of Bristol have struggled with the legacy of Colston, with some marking his birthday with celebrations and others demanding his statue be torn down and that schools, streets and one of our largest music venues, change their names to prevent what is seen as a celebration of one of Bristol’s greatest villains.

During a Black Lives Matter protest in June 2020, the statue of Colston was removed from its plinth by protesters and pushed into the Harbour close to Pero's Bridge. This extremely symbolic act was caught headlines around the world. The statue was pulled out of the water several days later and is now part of an exhibition at M Shed, along with placards from the day. Following these events the Colston name was removed from a nearby tower block and the lettering bearing his name was removed from the nearby concert hall, who were already in the process of changing their name.

Take the north-west exit from St. Augustine’s Parade to where Christmas Steps.

Image - Protest banners and placards at the plinth of the Colston statue, June 2020

6. Christmas Steps

Christmas Steps, the delightfully named crooked climb of ancient steps, has charmed visitors to Bristol for generations but behind the lovely facade of quirky shops and historic gas lamps hides a violent and dangerous history, one which once stained these steps red with blood.

Although the name is likely derived from the name Knyfesmith’s Street - deriving from the knife manufacturers that were once in abundance here, local legend proffers an alternative origin that the 'Knifesmiths' in question were violent muggers, hiding in the shadows of the many doorways that line this shambles of stone steps. The muggers would spring upon an unsuspecting victim and send them tumbling down the flight. If the fall alone did not kill them, a skilled knifesmith would finish the job in no time, whereupon the deceased victim would be robbed of all of his possessions.

Although the name is likely derived from the name Knyfesmith’s Street - deriving from the knife manufacturers that were once in abundance here, local legend proffers an alternative origin that the 'Knifesmiths' in question were violent muggers, hiding in the shadows of the many doorways that line this shambles of stone steps. The muggers would spring upon an unsuspecting victim and send them tumbling down the flight. If the fall alone did not kill them, a skilled knifesmith would finish the job in no time, whereupon the deceased victim would be robbed of all of his possessions.

Image - Christmas Steps

Whatever the explanation for the name of the street, it was certainly once a very dangerous corner of the city with merciless attacks being commonplace here. One legendary villain who once stalked the streets of Bristol was not recorded to have operated here, but the tiny figure of Jenkins Protheroe was notorious for choosing dark passageways such as this to operate in.

A robber and a murderer, Jenkins Protheroe, though an adult man, stood less than four feet high and assaulted his victims by lying in the street pretending to be a crying, injured child. Should a good samaritan come by, Protheroe would slash at their heels with his knife and rob them of whatever goods he could find. He was hanged in 1783 and his body remained in chains for months to rot away on Pembroke Road (then Gallows Road) until eventually the locals demanded his frightful corpse be taken away - following rumours that every night he would spring to life and dance maniacally in the street. His ghost is still said to haunt the road to this day.

From the top of these steps take a look around St. Bartholomew’s Church if you can. Inside you will find the headless statue of the Virgin Mary which, legend has it, was beheaded by Oliver Cromwell himself in a furious attack on Catholic imagery.

From the church, pass the Colston Almshouses on the left (built with the wealth of the notorious man himself as an act of charity to the poor of Bristol) and take the right turning at the Gryphon Bar to go down Trenchard Street.

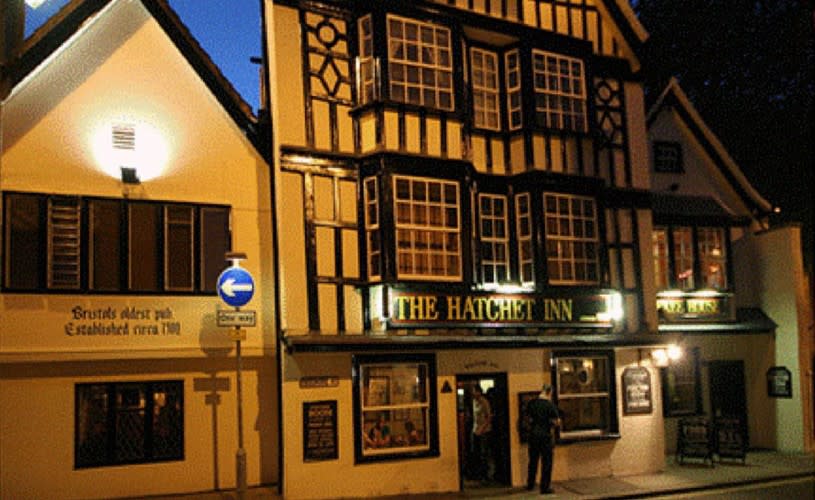

7. The Hatchet Inn

Built in 1606, The Hatchet is Bristol’s oldest pub and remains an offbeat, vibrant destination for those looking for a night out that’s a little unconventional. The tavern’s strangest claim to fame comes from its beautiful ancient door, now warped with age, it is believed that deep beneath the layers of paint the door was lined with the leathers of human skin.

Image - The Hatchet

As unlikely as it may seem, Bristol has a history of using human skin in creatively morbid ways, attained from the corpses of executed criminals. If true, the Hatchet would not be the only example of skin being used for decorative effect in the city, the most notorious case of all being that of John Horwood, a young man from Hanham who became infatuated with a woman named Elisa Balsom. She rejected his offers of courtship, believing him to be a member of the violent 'Cock Road Gang'. John reacted furiously and one day, upon seeing Elisa with another man in January of 1821, threw a stone which hit her in the temple. She later died in hospital and Horwood was found guilty of her murder, though some maintain that Elisa was probably more likely killed by attempts to revive her in the hospital.

Following his execution, his skin was cut from his body and his skeleton boiled and cleaned. It was given to Bristol University where it remained in a cupboard, still with the noose around the neck, until the 13 April 2011, when he was finally buried 190 years to the day following his hanging.

The skin that was cut from the body was tanned the day after his execution and used to bind together the notes on his trial. The book, still covered in Horwood’s skin, is on display at Bristol’s M Shed museum as a gruesome reminder of our city’s dark history.

That is the end of our tour through the macabre shadows of our city’s past. From here you can easily access Park Street and St. Augustine’s Parade for a well deserved drink or a bite to eat. I hope you enjoyed my journey through the city and I hope even more that none of our resident ghosts choose to follow you home…

About the author:

Charlie Revelle-Smith is an author of fiction and non-fiction books. He also curates the popular Weird Bristol feeds on Instagram which document the lesser-known history of Bristol. His books 'Weird Bristol' and 'More Weird Bristol' are available now.